23 Abr Leonardo da Vinci ‘Relics’ Discovered That Can Potentially Provide His DNA

Italian researchers say that they have found two “relics” belonging to Leonardo da Vinci, which may help in sourcing the DNA of the genius whose work typified the Renaissance.

The mysterious relics were traced during a decades-long genealogical study into Leonardo’s family.

Historian Agnese Sabato and Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale in Vinci, will announce their findings on Thursday at a conference in the Tuscan town of Vinci, where the artist was born in 1452.

“I can’t yet disclose the nature of these relics,” Vezzosi told Seeker. “I can only say that both are historically associated with Leonardo da Vinci. One is an object, the other is organic material.”

If genuine, the organic relic would represent Leonardo’s only known biological evidence.

It was believed that no traces were left of the painter, engineer, mathematician, philosopher and naturalist. The remains of Leonardo, who died in 1519 at the age of 67 in Amboise, France, are known to have been dispersed before the 19th century.

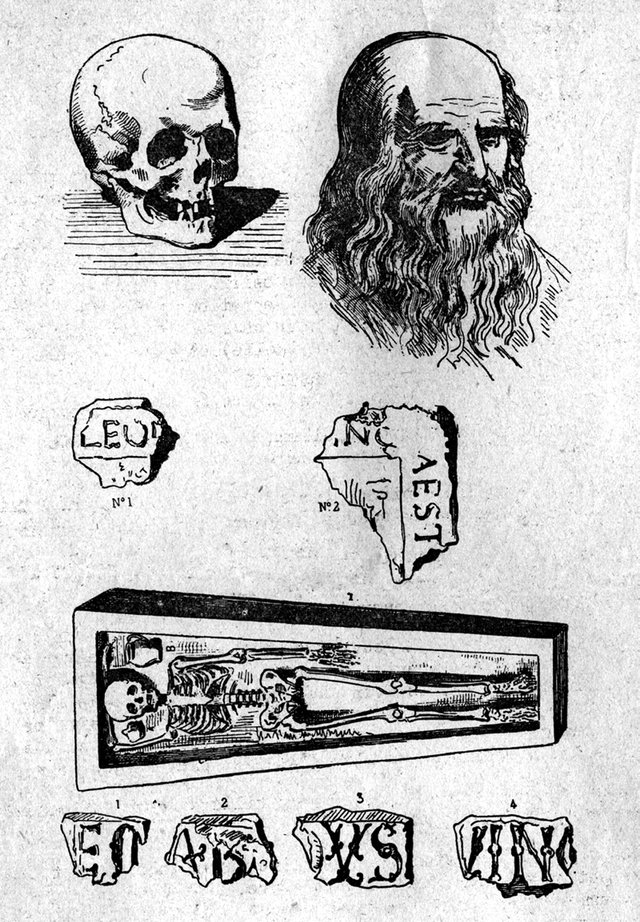

But in 1863 a skeleton and large skull were found at the site of the church of Saint-Florentin, where Leonardo was originally interred, which was plundered in the 16th century during religious wars and completely destroyed in 1808.

A stone inscription was unearthed near the skeleton. It read LEO DUS VINC, pointing to Leonardo’s name.

The bones attributed to Leonardo went lost for a decade. They were rediscovered in 1874 and reburied in the chapel of Saint-Hubert at the Château d’Amboise. There, a plaque correctly states that the grave contains Leonardo’s “presumed remains.”

Permission to exhume the bones for analysis has always been denied for ethical reasons. The organic relic claimed by the researchers was sourced from an unidentified private collector.

“We have verified its historical accuracy, and we can now say the relic is associated to the skeleton unearthed in 1863,” Sabato said.

Vezzosi and Sabato, who have founded an organization called Leonardo da Vinci Heritage to safeguard and promote his legacy, have been searching for biological traces of Leonardo since 2000. They began by scrutinizing the master’s paintings and manuscripts for his fingerprints.

“We pieced together an archive of hundreds of Leonardo’s fingerprints, hoping to get some biological material,” Vezzosi said. “At that time, cracking da Vinci’s DNA code was just a wild dream. Now it’s a real possibility.”

A crucial twist in the research occurred last year, when Vezzosi and Sabato announced the existence of dozens of Leonardo’s living descendants at a crowded conference in Vinci.

“It has been a long and exhausting research, as we had to deal with repeating names and confusing da Vinci and Vinci surnames,” Vezzosi said.

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of Ser Piero da Vinci, a Florentine legal notary, and Caterina, an enigmatic woman described in documents as being “the wife of Achattabriga di Piero del Vaccha da Vinci.» He had a sprawling family that included four stepmothers and as many as 24 half-brothers and half-sisters.

Since last year, Vezzosi and Sabato have updated the official da Vinci family tree, adding more than 150 names.

“The hunt for Leonardo DNA can now rely on a good, well-referenced genealogy,” Sabato told Seeker.

She explained that all of the direct descendants come from Leonardo’s father Ser Piero, since Caterina’s relatives appear to be lost in history.

“But we are working to track them down,” Sabato said. “We discovered that one of Caterina’s daughters had three daughters, so we are searching in this direction.”

Finding Caterina’s descendants — living or dead — might help in retrieving Leonardo’s mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down through the maternal line.

The researchers are now conferring with several international universities to begin a broader scientific investigation on the relics and Leonardo’s descendants. They plan to carry out DNA analysis on the relic and compare it to Leonardo’s newly discovered living descendants and to bones found in recently identified da Vinci burials throughout Tuscany.

The study is part of a wider project to find Leonardo’s DNA by 2019, to mark the 500th anniversary of his death.

“Overall, we have more than promising material to continue our research and isolate da Vinci’s DNA, 15 generations later,” Vezzosi said.

Even if it won’t be possible to retrieve any usable DNA from the relic, Leonardo’s reconstructed family tree still leaves hope to track down his Y chromosome.

Vezzosi and Sabato have found a direct and uninterrupted line which runs from Leonardo’s half-brother Domenico Matteo to living male descendants.

“If Domenico Matteo is Leonardo’s half-brother through the male line — they have the same biological father — then they should have the same Y chromosome type,” Turi King, a geneticist at the University of Leicester who carried out the DNA analysis on King Richard III, told Seeker.

”If Domenico then had a son, who had a son and so on down the generations, to a great, great [etc.] grandson who is alive today, then they should be able to carry out Y chromosome testing,” she added.

King, who is not involved in the study, warned that there is still the possibility of the male line being broken over such a large number of generations.

“In other words, there could have been a false paternity, where the biological father is not the recorded father, along the way,” she noted. “So the tree looks correct, but isn’t actually. And then there wouldn’t be a DNA match.”

But Vezzosi and Sabato remain confident that the reconstructed da Vinci family tree and the relics will provide a reliable basis to get fascinating insights into Leonardo’s life.

“We now have a solid Da Vinci genealogy. We also hope the organic relic yields enough usable DNA,” Vezzosi said.

“Whatever the case,” he added. “This relic has an extraordinary historic importance. We hope we will be soon able to put it on display.”

Fuente original: seeker.com